Some people believe excavating a piece of land is the same as grave robbing. Others see it as sacrilegious to disturb sacred ground. When properly done with the blessing of the community excavating can be a good thing, educating people of a forgotten history.

On Friday, September 2, 2022, students, and professors from the Anthropology and Archaeology departments of CCD, MSU of Denver and CU-Denver began a two-month archaeological dig of two carefully selected spots in the 9th Street Historic Park on the Auraria campus with a healing ceremony.

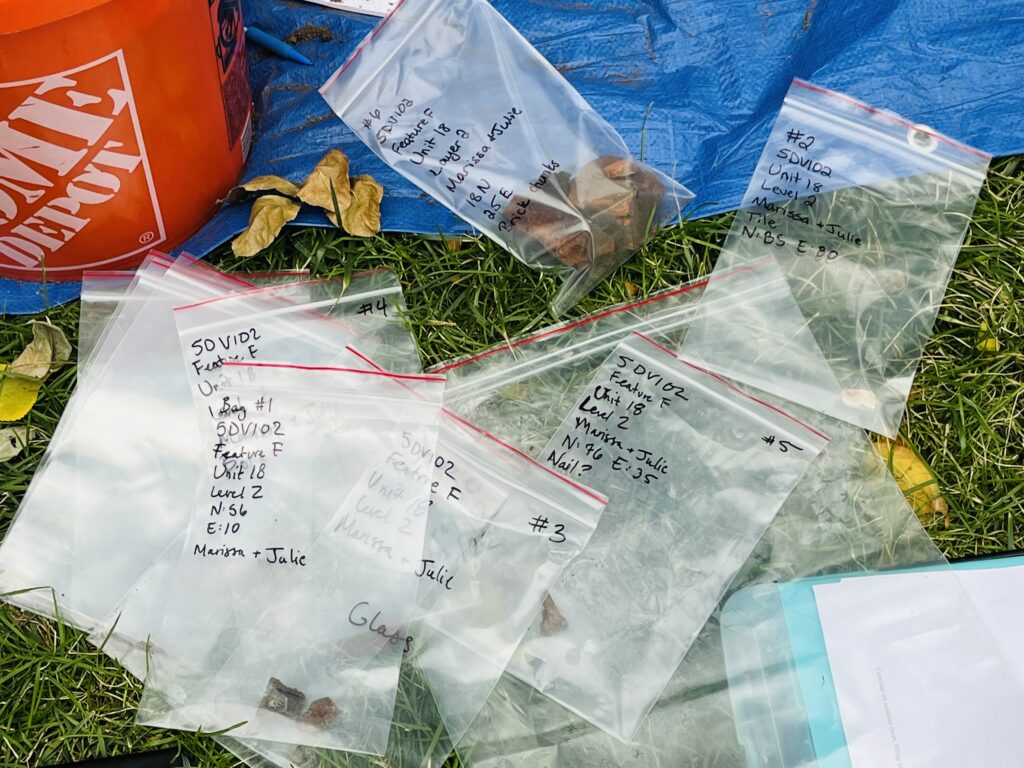

Every Friday for the next two months students would dig, sift through soil, measure, and document every artifact they would find. Their mission is to learn about Auraria’s history and possibly uncover artifacts they could place in a museum.

After years of discussion between the Auraria Historical Advisory Council, History Colorado and the University of Colorado, the conversations began to move towards how to educate others of the complicated history of this land.

A member of the Indigenous community that carried out the healing ceremony opening the archaeological dig project, was Michael Redman from the Northern Arapahoe Tribe. He shared that it was an honor to travel from Wyoming to pray and bless the land before they started digging. Redman reminded the large crowd gathered for the well-attended ceremony that this land was revered and used ages ago by his ancestors.

He reflected on the tantalizing possibility of finding any artifacts and how to properly handle them, “These objects are considered an inanimate object. They're alive, so they must be treated and cared for as a living, like a living person. You can't be disrespecting. That must be respected and must be honored. It must be taken cared, in handling them when they're found. Proper protocols must be taken care of and when they're discovered, and proper care must be put to them in place for them.”

Redman supported the idea of a Auraria campus museum where artifacts could be displayed, versus given back to the tribe, he explained, “Because a lot of our artifacts don't get put in a proper place while they do but they go to the museum in Chicago, or in DC and then who sees them? Nobody. Nobody sees them. If they if they could have them in a place and then agree with the tribes of this origin of this ground here. Arapaho and Cheyenne. Come together and whatever tribes that lived here, come together. And honor that.”

Students on this commuter campus may not be aware that before Auraria Higher Education Center (AHEC) was built, stood Auraria. This one-time mining settlement in the 1860s evolved into Denver’s oldest neighborhood eventually replaced by the Auraria campus during the 1960s and 1970s urban renewal movement.

During the effort to replace a thriving neighborhood with a campus, over 300 families were displaced, each given a promise that their descendants would receive a free education on the future campus. Although the construction was completed in 1976, the scholarship was not honored until 1988.

Sheila Perez Kendall, a displaced resident of Auraria, grew up in the Ninth District. She shared her memories of growing up and pointed out the different areas where businesses once stood.

This ground is still very sacred to Sheila and she feels strongly about the dig and establishing a museum. When asked about how she felt about the effort, she blinked away tears, put her hands over her heart, and replied, “Very touching to me. Acknowledged…it touches my heart.” Sheila is part of the Auraria Historical Advisory Council and strives to educate as many as she can about this story of gentrification.

One of the professors leading the excavation is Dr. Gene Wheaton from CCD’s Anthropology Department. He shared how the articles would explain to others how the people lived and tell their story. Students are just unaware they are walking through what was once Denver’s oldest neighborhood. He hopes they find artifacts to fill a museum to educate people on an important part of Denver history.

When asked why he was so adamant about getting the site excavated, he looked around the site and at students walking by. With a look of determination, he replied, “Because most of them don’t know.”

Respected community leader and educator, Virginia Castro, was also present during the healing ceremony. She supports the dig, placing artifacts in a museum and believes the excavation is just like digging up data. When asked what she hopes will happen from the excavation project she was optimistic. “I think good things are already happening. The students are enjoying themselves and they're learning a lot. I think this is just one more thing that brings the displaced peoples back to life, so to speak. You know, the fact that that they're coming to the campus and getting involved with us and talking about how we can memorialize the people that were forced out of there.”

Castro believes the museum should be an important portion of that education. When asked where the museum might be, she excitedly shared, “We're at the point right now, just waiting, to see which space we're going to get.”

She hopes the museum will be large enough to have a welcome center to assist descendants of displaced Aurarians to get connected with the scholarships. Virginia also believes the research and artifacts found come become a type of curriculum that would be available to incoming students. “New students that come on the campus, they will be able to access history of what happened on campus or in that space and everybody will eventually know the history of the campus and the people that lived there.”